The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren

How creatives lose agency in pop culture

Read the full text of The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren

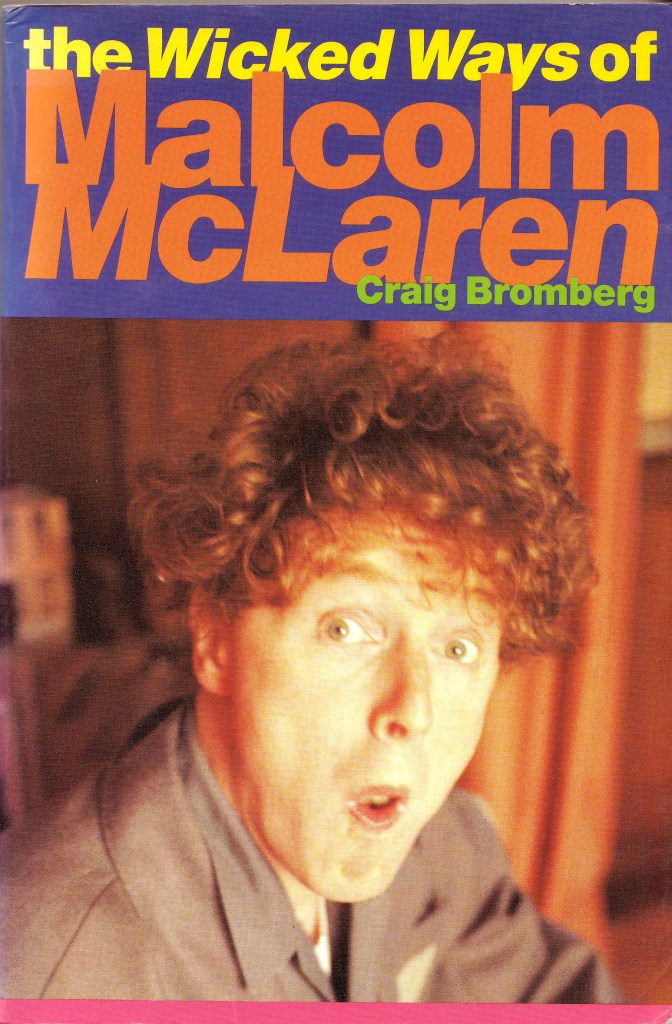

In 1987, Vanity Fair found itself with this Annie Liebovitz photo and assigned me to write a long caption. Three years later (1990) Harper & Row (US) and Omnibus Books (UK) published The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren, my biography of the manager of the Sex Pistols, Bow Wow Wow, Adam Ant, and husband of fashion designer Dame Vivienne Westwood.

When I first began the project, I considered McLaren to be the epitome of a post-modern artist-impresario hybrid who used music, fashion, media, and events to keep his “acts” on the front pages of British newspapers. For nearly a decade, he succeeded, pre-dating the attention economy by decades.

But as I researched The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren, I realized that McLaren’s luck with the Sex Pistols and Bow Wow Wow often came by claiming his collaborators’ agency, talent, and creativity—whether it was Johnny Rotten, Annabella Lwin, or even Richard Branson—as his own.

Sex Pistols — God Save The Queen

Bow Wow Wow — C30, C60, C90 Go!

Many, including McLaren himself, made the case for the manager as an artist following in the wake of Andy Warhol, but the legal and practical realities of McLaren’s engagement with the artists he represented was as their manager: booking shows, influencing their music and clothes, negotiating record and publishing deals, firing up the PR machine.

Despite all appearances, however, the Sex Pistols were not untalented cogs. It was their music, style, and attitude that turned listeners into agents of defiance against capitalism, religion, government, and even rock’n’roll.

Bow Wow Wow was similarly a product of McLaren’s imagination—dressing them as pirates (thanks to Westwood), posed as refugees from Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (thanks to Nick Egan), transgressing copyright law by promoting the lowly cassette tape as means of teenage rebellion (McLaren’s own insight). But their catchy, unique, and chart-topping music was their’s alone.

A similar case can be made for McLaren’s relationship with Westwood. Their collaboration was undoubtedly intense and real, but it speaks volumes that her work as a designer and activist flourished after their work together ended, while McLaren’s mark dimmed post-Pistols, no matter how hard he tried.

Fifty years on, the punk revolution of 1976 still excites debate. It’s sad that McLaren’s not around to jostle us, but the argument of The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren still stands. But now you can read the entire book, for free.

The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren